Blast from my Commodore 64 Past

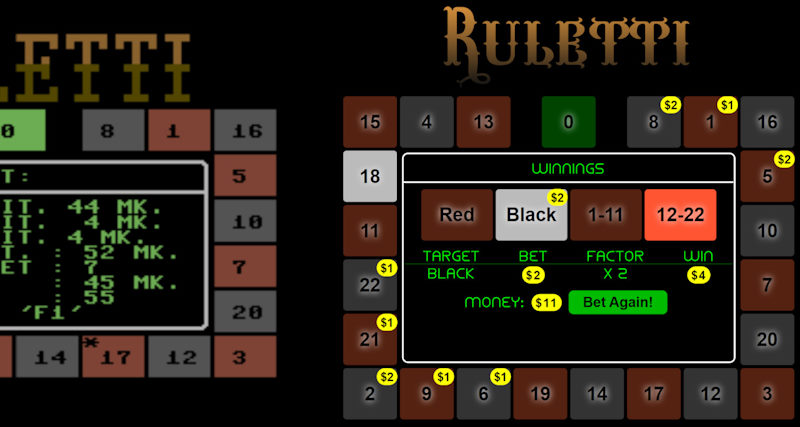

The little programs and games I wrote for VIC-20 and later Commodore 64 in the 1980's were eventually all lost. All, except one: A small Roulette-game that I got published in MikroBitti-magazine in the 1980's and is now playable again after 35 years.

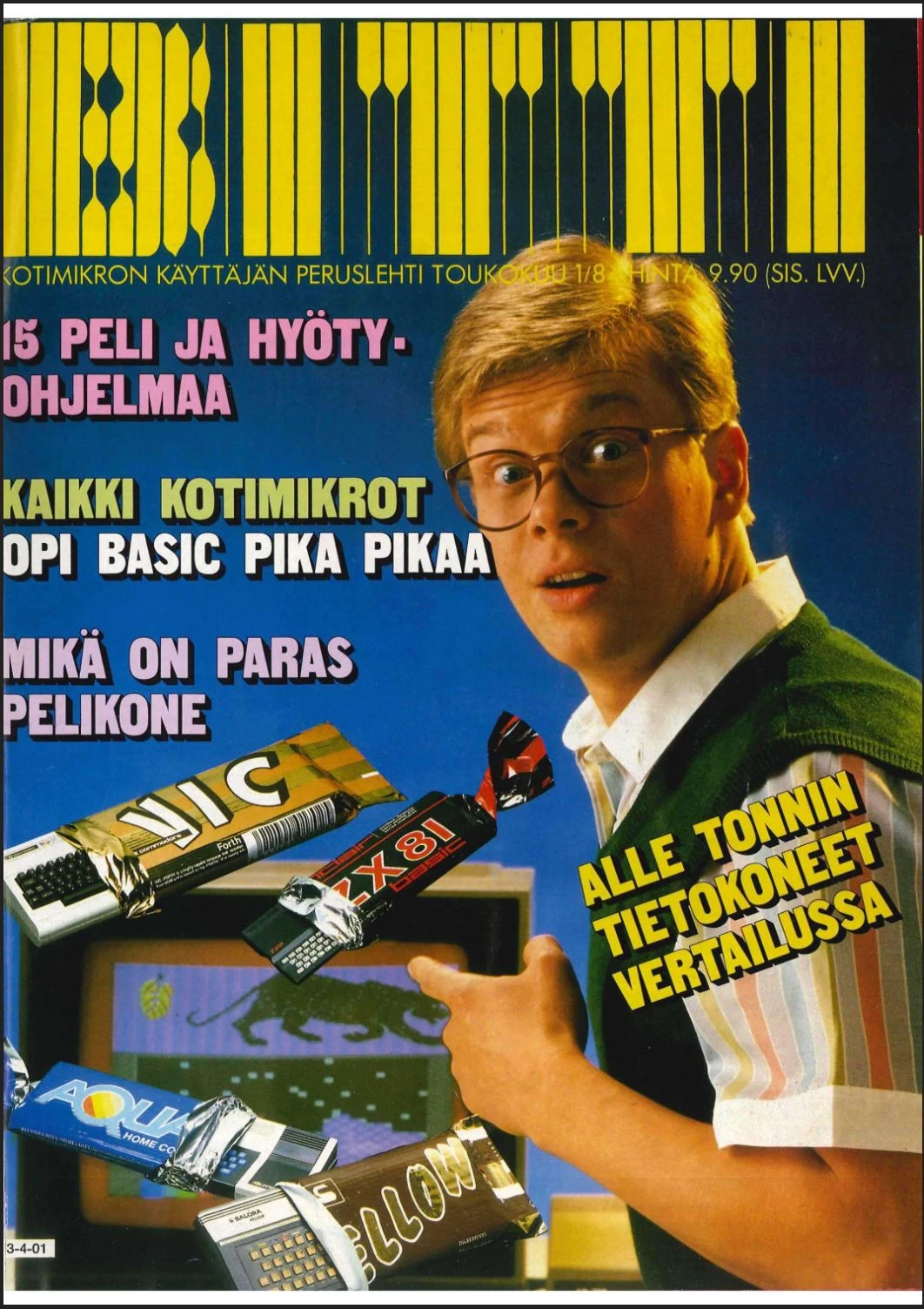

In the 1980's when my computer-hobby was started with VIC-20 and later Commodore 64, there was no Internet to publish hobby programs or study programming. During those years several computer hobby-magazines were launched and one of their main content was publishing full source-codes of small programs that readers were sending them. In Finland the legendary MikroBitti magazine started in July 1984 (when I was 10 years old) and I eagerly subscribed to it from the very first number, shown here:

Making of the Ruletti game

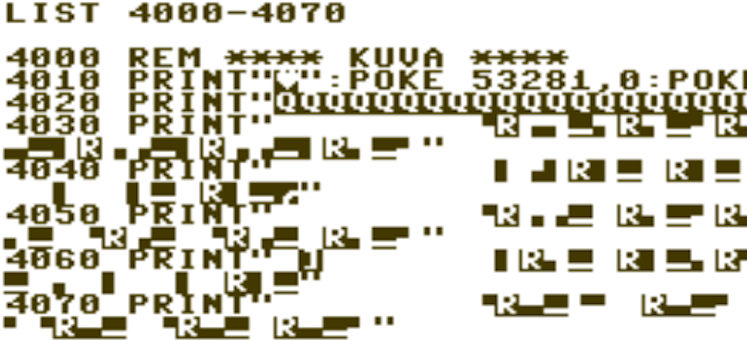

Like other hobbyists, I spent many tedious hours typing in programs from the listings published in MikroBitti, line by line, character by character, hoping to get the program working. This was by no means guaranteed since typing errors happened easily and it could be difficult to find out from incorrectly working program where the error was located. But typing in these listings was almost only way to get cheap software for one's machine, so we pushed forward. And in absence of other learning opportunities, this typing of all those programs from MikroBitti, looking at the examples and playing around modifying them was in the end an important way for me to learn programming.

As my skills grew I was writing more programs from scratch too, small utilities and games. I did not think at that time that preserving any of those would be important, so later in 1989 when I sold my Commodore64 and switched to Amiga 500, all those small programs I had done were lost forever. Except, fortunately, for one small game "Ruletti" (roulette) that I had written in April 1987 (when I was 13) and MikroBitti had published in their May 1988 magazine (when I was 14).

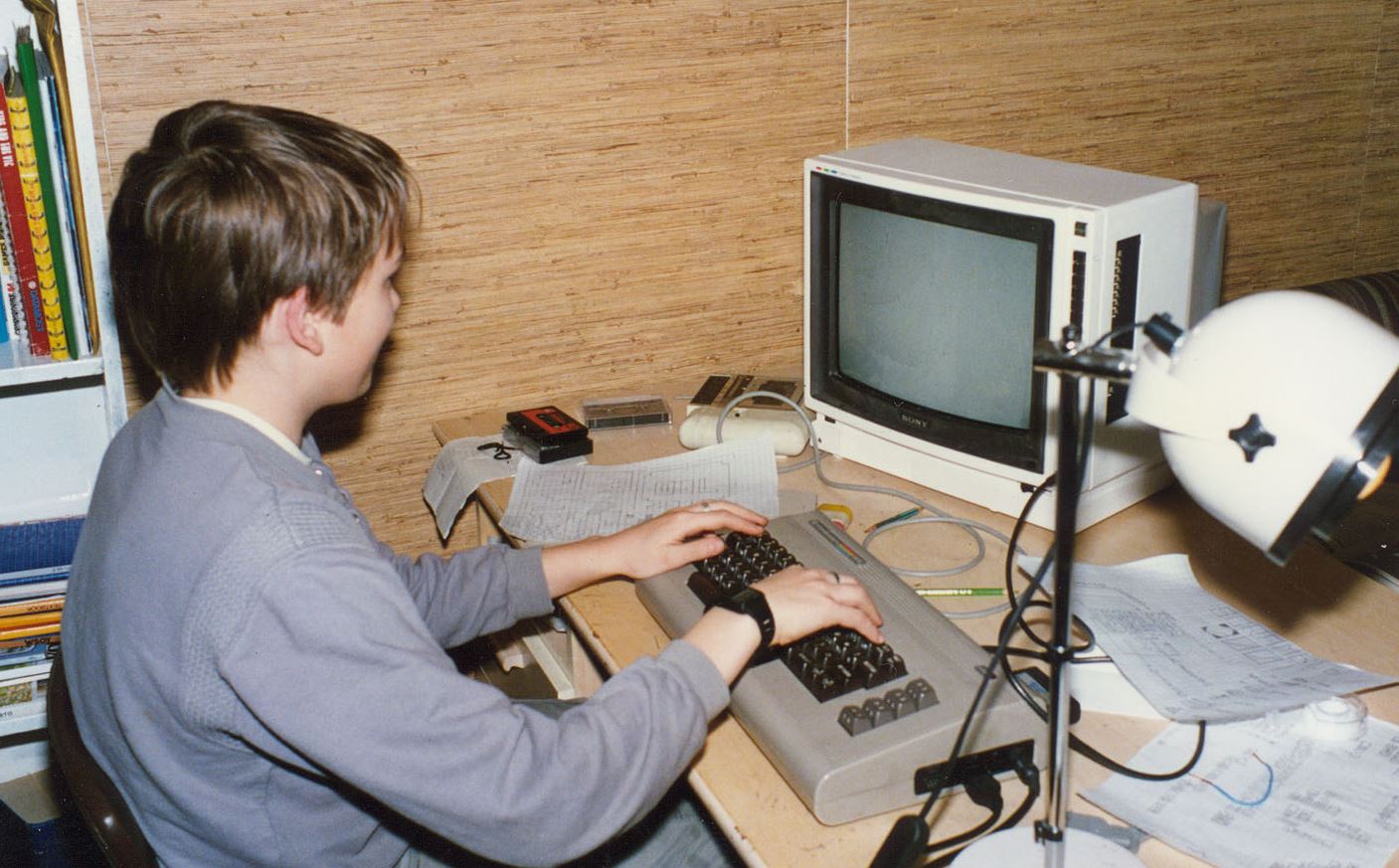

Below I am using my Commodore 64 in 1987, around the time of making Ruletti-game. Note the small CRT-TV used as the computer monitor and on its left-side a casette-drive and some C-casettes that I saved programs to:

Lost and Found

While I did not have a printed copy of the 1988/5 MikroBitti magazine anymore, its publisher luckily decided to cater to the emerging retro-nostalgia for Commodore 64 in 2010's by digitizing and offering through internet all the early MikroBitti magazines. Browsing through these in 2020 I was delighted to find my own program listing from the digitized version of the 1988/5 magazine starting from page 52:

File well preserved

I shared this happy finding with my Facebook friends and remarked that it would be nice to do the hard work of typing the program to Commodore 64 from the listing to once more see the game from 33 years ago. While I don't have physical Commodore 64 any more, there are several good emulators available, including web/Javascript-based emulator that can be used without any installation.

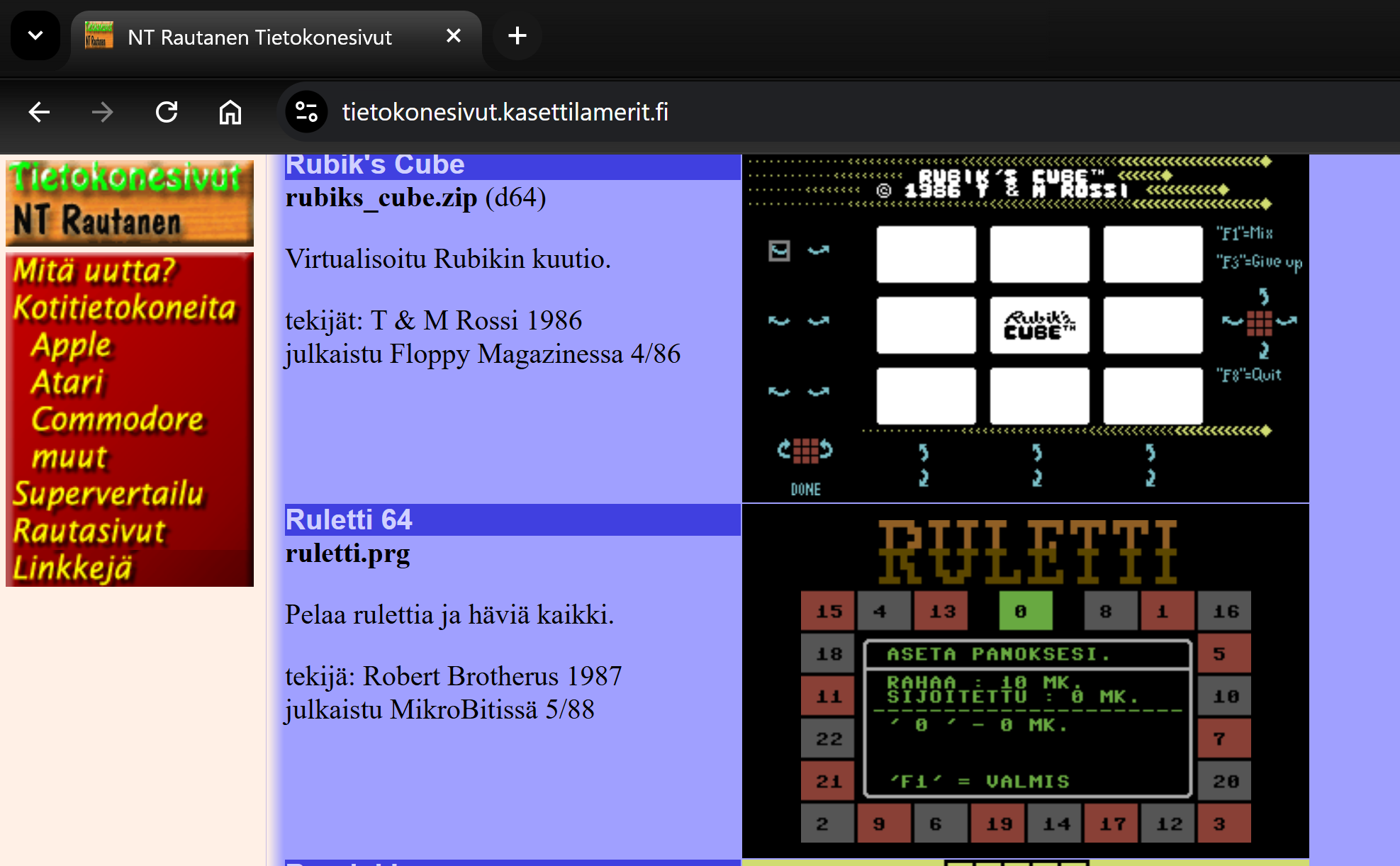

By a feat of luck one of my Facebook acquaintances knew an easier possibility. It turns out that in 1987 MikroBitti started selling to its subscribers yearly program-listing collections on floppy-disks, so readers could play the games without typing them in. And it turned out that a Commodore hobbyist Niila T Rautanen had been collecting all these floppies and creating and internet archive of them! My friend knew of this archive and sent me its link where after searching the Commodore 64 games section found my game, with screenshot and download-link for the program file:

To my delight and amazement just moments later I had been able to download, launch and play ruletti.prg on the web/Javascript-based emulator in browser! 😊

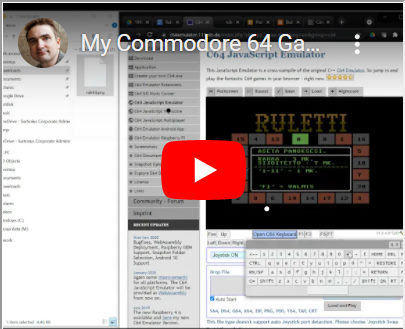

Here is a small video I recorded of starting the game in emulator and playing some rounds:

If you want to try playing the game in this way, following instructions are needed since the game texts are in Finnish:

- In the emulator, click "Open C64 keyboard" and use that virtual keyboard to interact with the emulator. Mapping of the PC keyboard to the C64 keys is not reliable.

- In the starting screen press F1 to proceed and then again F1 to accept 10 mk as the starting money.

- In the betting stage, use "/" and "@" keys to switch between betting options which are numbers 0-22 (which will return money with 22x-factor), red/black and small/big (which return money with 2x-factor)

- After selecting item to bet on, use "+" and "-" keys to adjust amount of money to bet

- When ready press F1 which starts rotating the roulette light

- After rotation stops, you will get winnings added to your base money.

If you have money left you can continue with F1.

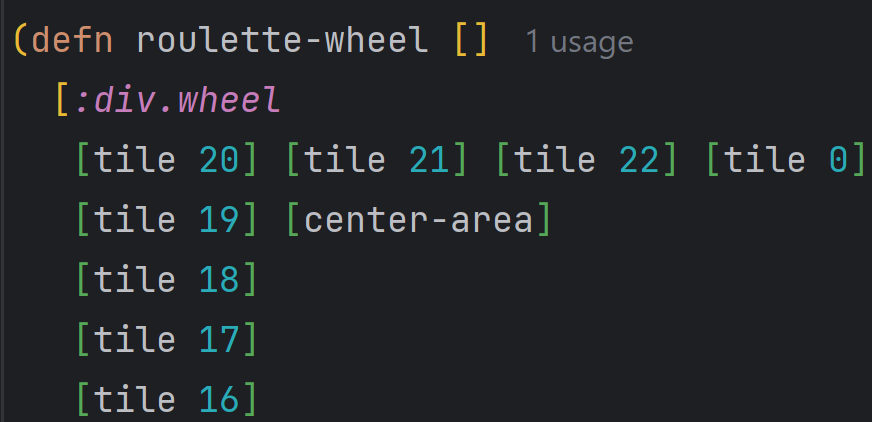

Diving to the old code

For the programming-oriented, I later wrote another post reviewing the code of Ruletti 64, looking at challenges with the limited Commodore 64 Basic.